But actually, I’m serious.

People are rightly concerned about what is going on in the W3C with DRM , as couched in the Encrypted Media Extensions (EME) proposal. Please read Henri Sivonen’s explanation of EME if you haven’t yet.

As usual for us here at Mozilla , we want to start by addressing what is best for individual users and therefore what’s best for the Open Web , which in turn depends in large part on many interoperating browsers , and also on open source implementations with a significant combination by number and market share among those browsers.

We see DRM in general as profoundly hostile to all three of: users, open source software, and browser vendors who aren’t also DRM vendors.

Currently, users can play content that is subject to DRM restrictions using Firefox if they install NPAPI plugins, really Flash and Silverlight at this point. While we are not in favor of DRM, we do hear from many users who want to watch streaming movies to which they rent access rather than “buy to own”. The conspicuous example is Netflix , which currently uses Silverlight, but plans to use EME in HTML5.

(UPDATE: Netflix is using EME already in IE11 on Windows 8.1 without Silverlight. And Chrome OS has deployed EME as well. Apple too, in Mavericks.)

What the W3C is entertaining, due to Netflix, Google, and Microsoft’s efforts, is the EME API , which introduces new and non-standard plugins that are neither Silverlight nor Flash, called Content Decryption Modules (CDM for short), into HTML5. We see serious problems with this approach. One is that the W3C apparently will not specify the CDM, so each browser may end up having its own system.

We are working to get Mozilla and all our users on the right side of this proposed API. We are not just going to say that users cannot have access to streaming Hollywood movies, as that is a good way to lose market share and not have any product with which to uphold our mission.

Mozilla’s mission requires us to build products that users love — Firefox , Firefox for Android , Firefox OS , and Firefox Marketplace are four examples — with enough total share to influence developers, and therefore standards. Given the forces at play, we have to consider EME carefully, not reject it outright or embrace it in full.

Again, we have never categorically rejected plugins, including those with their own DRM subsystems.

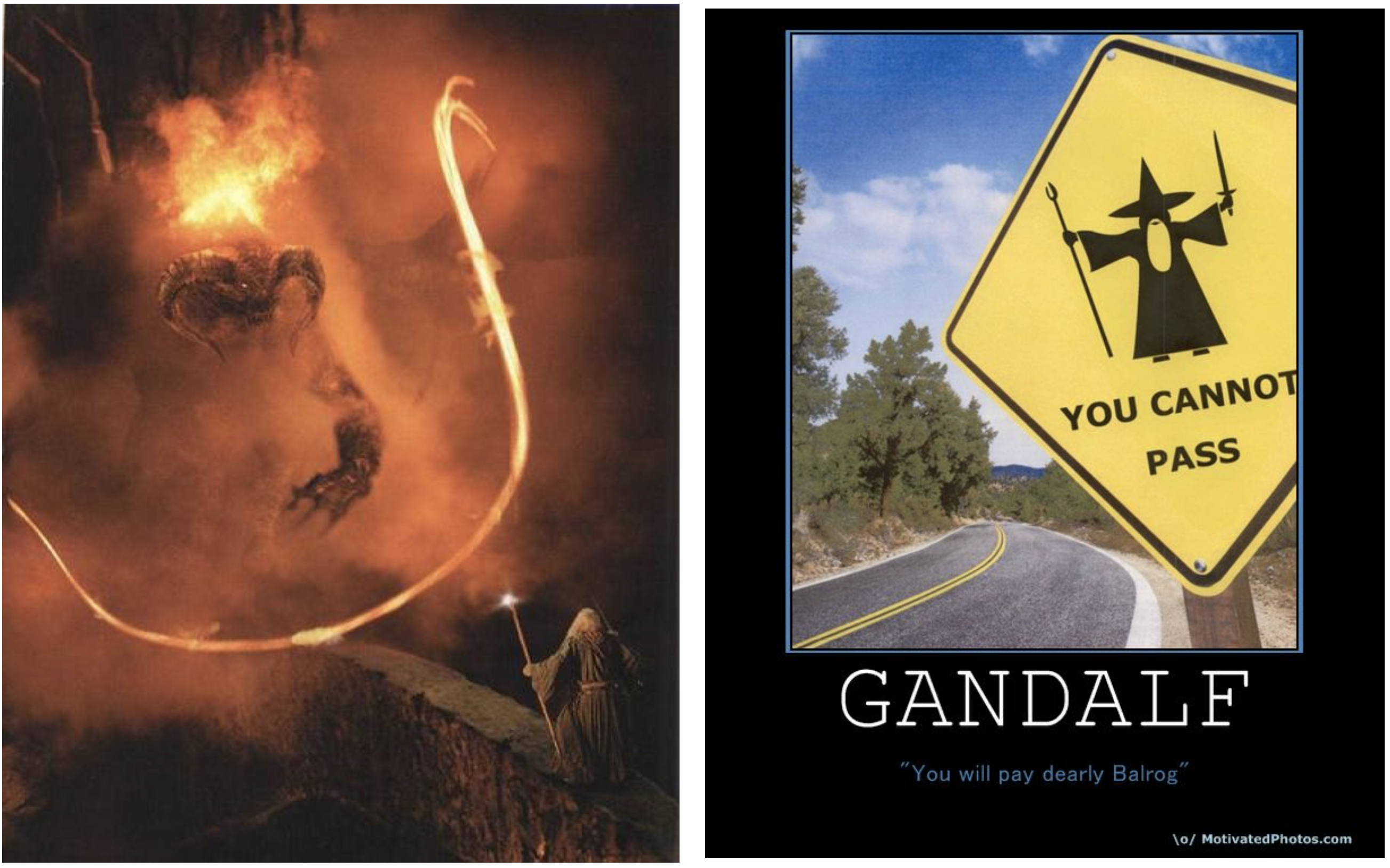

However, the W3C willfully underspecifying DRM in HTML5 is quite a different matter from browsers having to support several legacy plugins. Here is a narrow bridge on which to stand and fight — and perhaps fall, but (like Gandalf) live again and prevail in the longer run. If we lose this battle, there will be others where the world needs Mozilla.

By now it should be clear why we view DRM as bad for users, open source, and alternative browser vendors:

- Users: DRM is technically a contradiction , which leads directly to legal restraints against fair use and other user interests (e.g., accessibility).

- Open source: Projects such as mozilla.org cannot implement a robust and Hollywood-compliant CDM black box inside the EME API container using open source software.

- Alternative browser vendors: CDMs are analogous to ActiveX components from the bad old days: different for each OS and possibly even available only to the OS’s default browser.

I continue to collaborate with others, including some in Hollywood, on watermarking, not DRM . More on that in a future post.

/be